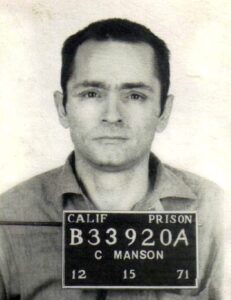

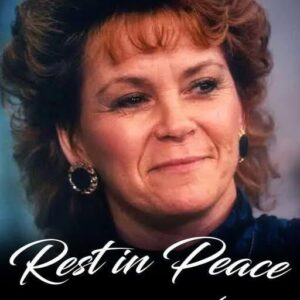

The photograph is unsettling in its simplicity. A young boy stares into the camera with a face that could belong to any child growing up in mid-20th-century America. There is nothing visibly threatening in his expression. No hint of the darkness that would later define his name. Yet history would come to know that boy as Charles Manson, a figure whose legacy became synonymous with manipulation, cruelty, and murder. His story forces an uncomfortable question: how does a child who begins life so unremarkably transform into one of the most infamous symbols of evil in modern history?

Understanding Manson’s life does not excuse his actions. But examining the forces that shaped him—abandonment, instability, violence, and a lifelong pattern of rejection—offers insight into how deeply damaged individuals can grow into destructive forces when their early suffering is never addressed.

A Birth Marked by Absence and Instability

Charles Manson was born on November 12, 1934, in Cincinnati, to a sixteen-year-old mother named Kathleen Maddox. From the beginning, his life was marked by absence. His father, a career con artist, vanished before Charles was even born. The identity of that father remained unclear, and the lack of a stable parental figure would become a recurring theme throughout Manson’s childhood.

Kathleen herself was deeply troubled. Struggling with alcoholism, impulsivity, and criminal behavior, she was ill-equipped to provide consistent care. When Charles was just four years old, she was arrested for assault and robbery, crimes she committed alongside her brother Luther. During the incident, Luther smashed a bottle over a man’s head before stealing his car. Luther was sentenced to ten years in prison. Kathleen received five years, serving only three.

With his mother incarcerated, Charles was sent to live with his aunt and uncle in McMechen. This relocation uprooted him yet again, reinforcing the instability that would dominate his early years.

A Child Who Learned Early That No One Stayed

Though visits with his mother were mandatory while she was imprisoned, young Charles often resisted them. These visits were confusing and emotionally painful—reminders of a bond that existed in theory but not in practice. When Kathleen was released from prison, Charles later described the first weeks together as the happiest period of his life. For a brief moment, he believed he might finally have the mother he longed for.

That hope did not last.

Kathleen soon returned to heavy drinking. She would disappear for days at a time, leaving Charles in the care of whoever happened to be available. Babysitters rotated constantly. There was no routine, no consistency, no emotional safety. Eventually, she decided she could no longer handle him and sent him to reform school.

By his own later accounts, by age nine he had already committed acts of arson, setting one of his schools on fire. Truancy and petty theft became routine. These behaviors were not isolated mischief; they were early signs of a child acting out in an environment where attention—even negative attention—was better than neglect.

Institutions That Punished Instead of Protected

At thirteen, Charles was sent to the Gibault School for Boys in Terre Haute, Indiana, a Catholic institution run by priests who believed in strict discipline. Beatings for minor infractions were common. For a boy already shaped by abandonment, this environment reinforced a worldview rooted in fear and resentment rather than accountability or care.

Manson ran away. He first returned to his mother, who promptly sent him back. He ran again—this time to Indianapolis—where he survived through burglaries, theft, and sleeping under bridges or in wooded areas. Childhood for him was not about learning or growth. It was about survival.

Arrests followed. Juvenile detention centers became familiar territory. At a school in Omaha, he and another boy stole a car within four days of arrival and committed armed robberies on their way to visit a relative. Crime was no longer rebellion—it was apprenticeship.

During this period, Manson developed a tactic he later called “the insane game.” When threatened by stronger individuals, he would shriek, contort his face, and flail his arms wildly to convince them he was mentally unstable. It worked. This early performance would foreshadow his later mastery of psychological manipulation.

The Making of an Aggressively Antisocial Mind

For a brief moment, Manson attempted to live a conventional life. He worked as a Western Union messenger, holding down a job and appearing functional. But the structure of normalcy could not compete with the patterns already ingrained in him. He returned quickly to crime.

Psychiatric evaluations during this time described him as “aggressively anti-social.” His behavior escalated in severity and cruelty. While serving time at a federal reformatory, he was arrested for sexually assaulting another boy at knifepoint. He repeatedly engaged in sexual acts with inmates, leading to transfers to maximum-security facilities.

These environments did not rehabilitate him. They hardened him. They reminded him, again and again, that power belonged to those who could dominate others—physically, psychologically, or emotionally.

Prison as a Training Ground for Manipulation

One of the most significant periods in Manson’s development occurred during his incarceration at McNeil Island Penitentiary in Washington State. There, he immersed himself in books on psychology, philosophy, and self-help. He studied hypnosis, persuasion, and influence.

He practiced these techniques on fellow inmates, including future actor Danny Trejo, who would later recall Manson’s unsettling charisma and manipulative abilities.

Prison did not suppress Manson’s need for control. It refined it.

The Illusion of Reinvention and the Lure of Fame

Upon his release, Manson drifted through marriages, theft, and schemes. He moved across states in stolen cars. He sought dominance over women, attempting to establish prostitution rings and forming relationships with underage girls—crimes that repeatedly landed him back behind bars.

Yet beneath the criminal behavior was another hunger: recognition.

In the mid-1960s, Manson attempted to break into the West Coast music scene. He fancied himself a songwriter and performer, believing fame would finally validate him. He befriended Dennis Wilson of The Beach Boys, briefly entering a world of wealth and celebrity.

But success never came. His music career stalled. Doors closed. Rejection, once again, became the defining theme.

Delusion, Control, and the Birth of a Cult

By the late 1960s, Manson’s mental state deteriorated dramatically. He gathered a group of vulnerable young followers—many disillusioned, searching for meaning, or estranged from family. To them, he presented himself as a prophet, a messiah, a voice of truth in a broken world.

He claimed the Beatles were sending him coded messages through their music. From these delusions emerged the concept of “Helter Skelter,” a coming race war in which society would collapse. Manson believed he and his followers would survive in a desert bunker, then emerge to rule over a devastated world.

This was not madness alone. It was madness paired with manipulation.

The Murders That Shocked the World

In August 1969, Manson’s ideology turned lethal. He ordered his followers to commit acts of unspeakable violence. Actress Sharon Tate, eight months pregnant, was brutally murdered in her home along with four others. The following night, Leno and Rosemary LaBianca were killed in their own residence.

According to follower Tex Watson, the instruction was clear: “Totally destroy everyone in the house. Make it as gruesome as you can.”

Though Manson did not physically carry out the killings, prosecutors argued that his teachings, commands, and psychological control constituted conspiracy to murder.

A Name That Became a Metaphor for Evil

Manson was convicted of multiple murders and sentenced to death in 1971. After California abolished the death penalty, his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.

Prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi famously stated, “The very name Manson has become a metaphor for evil—and evil has its allure.”

Despite applying for parole twelve times, Manson was never released. He died in prison in 2017 at the age of 83, following cardiac arrest complicated by colon cancer.

The Legacy That Refuses to Fade

Even in death, Charles Manson’s influence lingers. His name appears in music, film, documentaries, and books. His story continues to disturb not only because of the crimes, but because of the uncomfortable truth it exposes: evil is not always born fully formed. Sometimes, it is shaped—slowly, painfully—by neglect, violence, and a society that fails to intervene when damage is still reversible.

The boy in that photograph did not look like a monster.

But history shows us that when innocence is left unprotected, when trauma is untreated, and when cruelty becomes normalized, the transformation can be catastrophic.

Charles Manson’s life stands as a grim reminder that evil does not emerge in a vacuum. It grows where care is absent, where pain is ignored, and where power replaces compassion.